A legendary movie, almost a pipe dream , an obsession that has inhabited Gilliam’s head for decades.

Margherita Fontana and Carlotta Magistris tell us their surreal experience, as always happens with Gilliam’s cinematography.

The Man Who Killed Don Quijote – as seen by Margherita Fontana

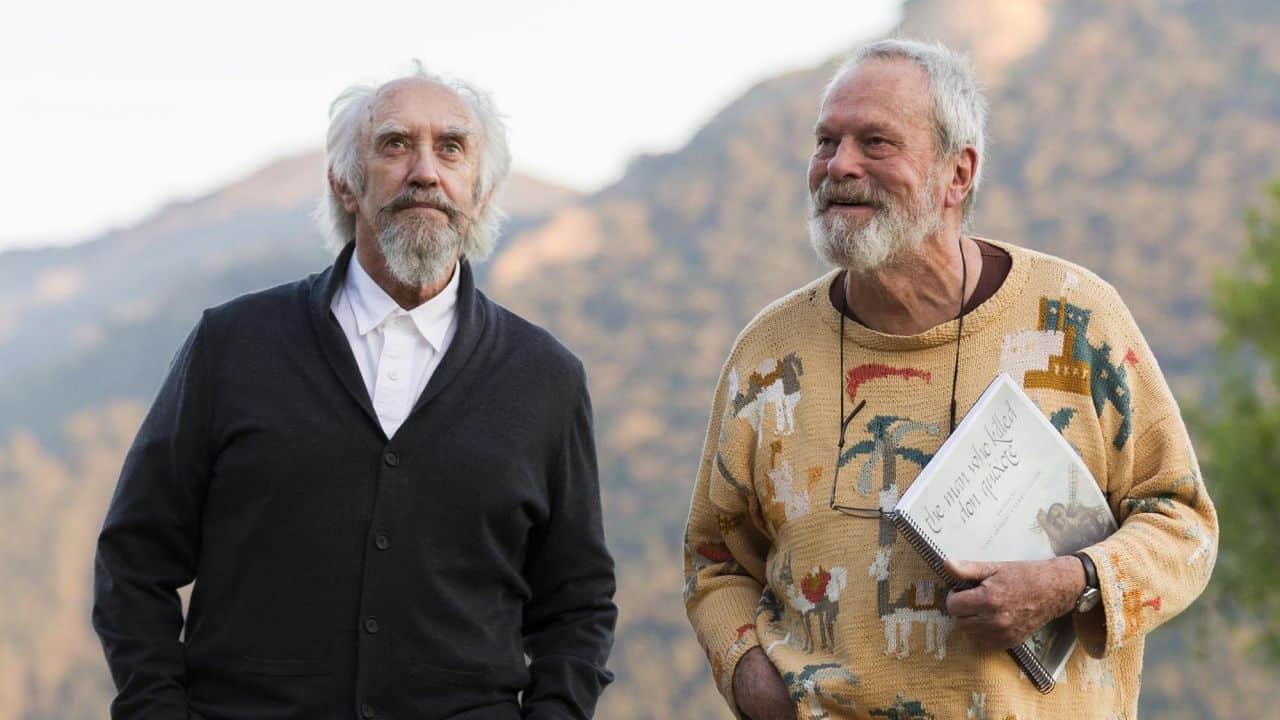

The latest film by Terry Gilliam is literally, so to speak, is latest effort: presented at Cannes, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote comes to light after 29 years of personal and financial struggles – which by the way have become a documentary themselves (Lost in La Mancha, 2002). This whole thing sounds curious since the film seems to be precisely about that: by weaving together biography and fiction, past and present, as well as different cinematographic languages (Hollywood and student indie film, colour and B/N, to name but two), the film describes the complexity of the creative process, while paying homage to the classic by Cervantes. In Gilliam’s disturbing and satirical universe the privileged point of view is not the protagonist’s one (Jonathan Pryce, with Gilliam in his masterpiece Brazil) , but his esquire Sancho Panza’s (Adam Driver), the director’s alter ego. Maybe that’s because only this lateral perspective can reveal what it means to shape a story, an idea, a film: a desperate journey through a dangerous territory, in the pursuit of what seems to be only a misunderstanding of the real.

The Man Who Killed Don Quijote – as seen by Carlotta Magistris

Well-known example of development hell, with eight attempts in twenty years, The Man who killed Don Quixote is the story of a young spot director (Adam Driver) who falls victim of his own work, meeting again – many years after he shot his degree movie in a small Spanish country based on the Don Chisciotte by Cervantes – the people who took part in his work, which he left full of expectations. What he finds is a series of deviated personalities, in particular the old man who interpreted Don Quixote, consciously or not persuaded of his being Don Quixote himself, confusing the main character with Sancho Panza and creating many alienated jokes. Going deeper, this is a reflection about doing cinema, about illusion and the loss of illusion, an identity crisis and individual growth; an ambitious and magniloquent work which remains effective for the ones who love this movie genre, losing itself in a narrative style typical of Gilliam’s cinema, made of paradoxical situations and belly irony but not opening the door to an eventual other kind of public, who toils to get over the pressing and almost repetitive narrative style to retrace deeply the macro reflexivity of the story.

Commenti recenti